It is January 19th, dear reader, which, as I’m sure you know by this point in our relationship, means that somewhere in the vast, spiraling ether of the literary afterlife – a place I imagine looks suspiciously like a Baltimore gutter circa 1849 and smells faintly of amontillado and laudanum – Edgar Allan Poe is turning 217. Or he would be, had he not shuffled off this mortal coil in a weird delirium tremens fugue state at the ripe old age of 40. But we are not here to mourn the brevity of the fuse; we are here to celebrate the explosive, terrifying bang.

To be clear from the start: without Poe, modern literature is basically just a series of polite tea parties where nothing bleeds.

Before Poe, “scary” stories were mostly just moralistic claptrap about why you shouldn’t wander into the woods or stiff peers in castles rattling chains. Poe took those chains and strangled his reader with them while whispering sweet nothings about the inevitability of premature burial. He was the original architect of the American Nightmare who looked at the burgeoning optimism of the 19th century and said, “Yes, but what if a bird flew into your room and screamed at you about your dead girlfriend until you went insane?”

Consider the sheer, unadulterated audacity of the man. He invented the detective story – invented it, wholesale, out of thin air – with “The Murders in the Rue Morgue.” He gave us C. Auguste Dupin, the ur-Holmes prototype for every socially maladjusted genius sleuth from Baker Street to whatever Scandi-noir police procedural you’re currently binging on Netflix. And he did it not because he loved the law, but because he was obsessed with the puzzle, with the friction between the rational mind and the irrational universe.

And honestly, if you haven’t tried to read “The Fall of the House of Usher” while nursing a hangover that feels like a nine-inch nail through the frontal lobe, have you even really read it? The sensory hypersensitivity of Roderick Usher is not just a gothic trope: it is the definitive literary depiction of the Sunday Morning Fear.

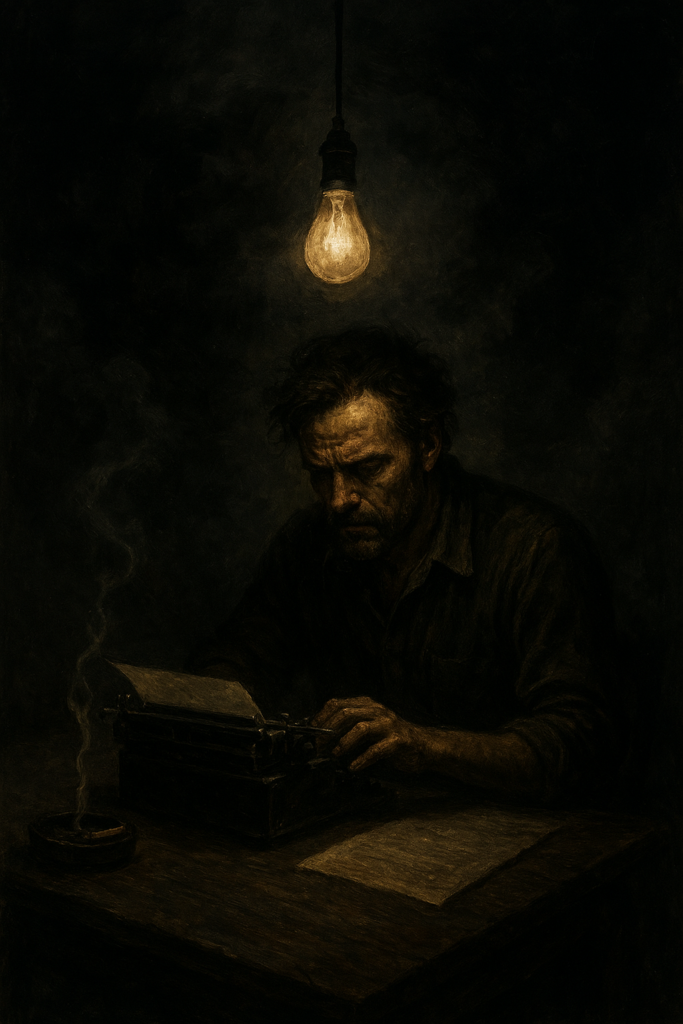

We celebrate him today not because he was a saint – by all accounts, he was a disaster of a human being, a walking catastrophe of bad debts, worse decisions, and a liver that was essentially waving a white flag for two decades – but because he had the balls to stare into the abyss and take meticulous notes. He understood that the monster isn’t under the bed: the monster is in your head, and it is probably significantly smarter than you are.

So here’s to you, Edgar, you gloomy, brilliant wretch. I hope wherever you are, the bells are ringing, the raven has shut its beak for five minutes, and the cask is tapped.

Cheers.

N.P.: “Death Waltz” – Adam Hurst