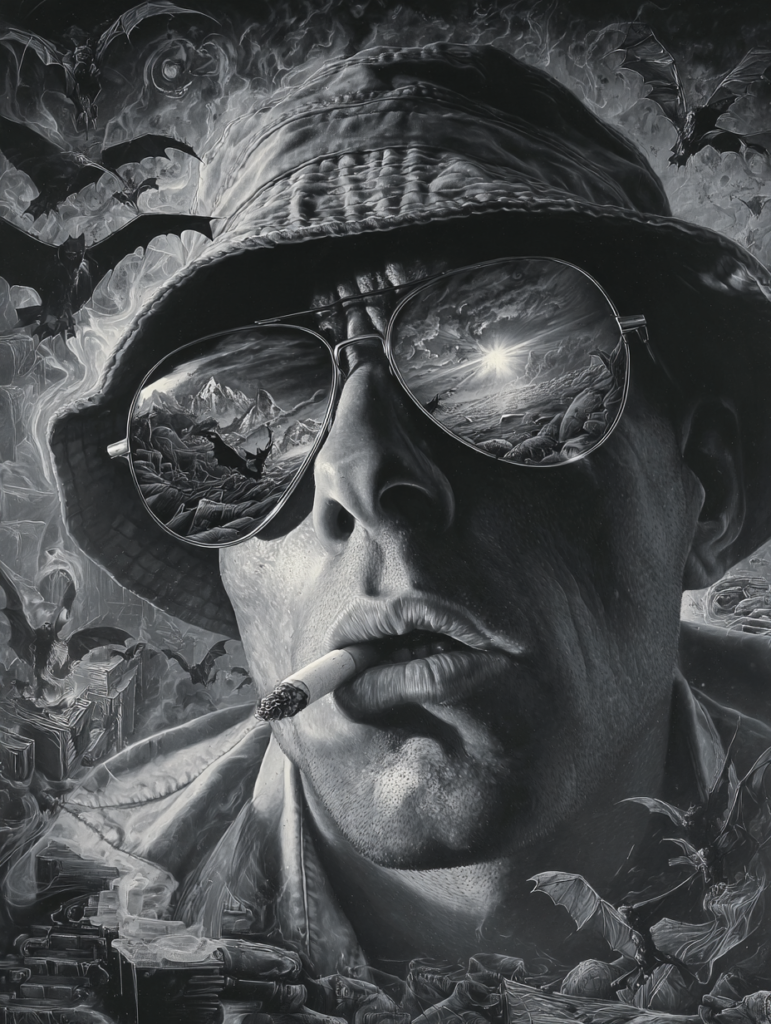

On February 20, 2005, Hunter S. Thompson – doctor of gonzo, lifelong enemy of dullness, consumer of staggering quantities of Chivas Regal and Dunhill cigarettes and whatever else happened to be within arm’s reach – put a .45 to his head in the kitchen at Owl Farm and ended the whole messy, exhilarating, frequently terrifying ride at sixty-seven. The act was not, strictly speaking, a surprise to anyone who’d followed the trajectory even halfway closely. The man had spent decades living at a pitch of psychopathic intensity that most people can only approximate on particularly bad acid trips or in the third act of particularly bad action movies. He embodied the mayhem he wrote about…courted it, occasionally tried to outrun it on two wheels with a bottle in one hand and a typewriter in the other. And then, when the body finally began to betray him – broken leg, hip replacement, the creeping boredom that arrives when the fun starts costing more than it delivers – he decided, with characteristic decisiveness, that Enough was Enough.

The note he left, scrawled in black marker and discovered by his wife Anita four days earlier, bore the title “Football Season Is Over.” It reads, in full:

No More Games. No More Bombs. No More Walking. No More Fun. No More Swimming. 67. That is 17 years past 50. 17 more than I needed or wanted. Boring. I am always bitchy. No Fun – for anybody. 67. You are getting Greedy. Act your old age. Relax – This won’t hurt.

There is something almost embarrassingly elegant about the brevity, the flat refusal to sentimentalize or explain or apologize. No long confession, no hand-wringing over legacy or loved ones left behind, just a curt ledger of what’s finished and a curt permission slip for the rest of us to stop pretending it could have gone any other way. The line about being “always bitchy” lands with the same casual brutality as one of his best rants; even in signing off he couldn’t resist the jab. And that final “Relax – This won’t hurt” functions as both reassurance and punchline, the last smirk from a man who spent his life grinning into the teeth of American nightmares.

The funeral, such as it was, took place months later on August 20, 2005, and it was exactly the sort of spectacular, over-the-top valediction the corpus of work demanded. Johnny Depp – friend, portrayer of the good doctor on screen, and apparently the only person in Hollywood with both the cash and the stomach for it – footed the bill (rumored at three million dollars) for a 150-foot tower erected on the property. Atop the tower sat a giant fist, with two thumbs, of course, clutching a peyote button: Thompson’s personal sigil, obscene and defiant. The ashes were loaded into a cannon and fired skyward amid fireworks while a crowd of celebrities, politicians, and hangers-on watched the gray cloud disperse over Woody Creek. It was ridiculous, vulgar, expensive, and oddly moving – the gold standard, really, for what a literary exit can look like when the author has spent a lifetime insisting that literature ought to be dangerous, participatory, and at least a little bit insane.

What makes the whole business feel so indelibly badass isn’t the violence of the death itself (plenty of people shoot themselves; precious few turn the aftermath into performance art), but the absolute refusal to let age or decay or the ordinary humiliations of the body dictate the terms. Thompson had always insisted on control – of the narrative, of the chemicals, of the chaos – and in the end he seized control of the ending too. No slow fade into irrelevance, no pathetic decline into nostalgia tours or university lectures. Just a clean break, a final “No more,” and then the cannon roar sending what was left of him back into the thin mountain air he loved.

We are left, inevitably, with the question of whether it was tragic or triumphant or some irreducible mixture of both. The easy answer is tragedy: a brilliant mind undone by pain, depression, the long tail of excess. But the easy answer feels wrong here, inadequate to the scale of the life. Thompson didn’t drift into The Void; he aimed himself at it, eyes open, middle finger raised. And if that isn’t the ultimate fuck-you to entropy, to the slow grinding down of everything interesting, then it’s hard to imagine what would be.

So here’s to The Doctor, who lived louder and weirder and more dangerously than almost anyone, and who left on his own terms with a note that reads like a haiku written by a man too impatient for poetry. The bats are everywhere. But the Doctor is out. He saw the game was rigged, the season was over, and he punched his own ticket. And in doing so, he left behind the ultimate lesson: if you’re going to go, go out on your own goddamn terms, with a bang big enough to echo through eternity.

N.P.: “Weird and Twisted Nights” – Hunter S. Thompson

Somebody thought they could leave a comment!