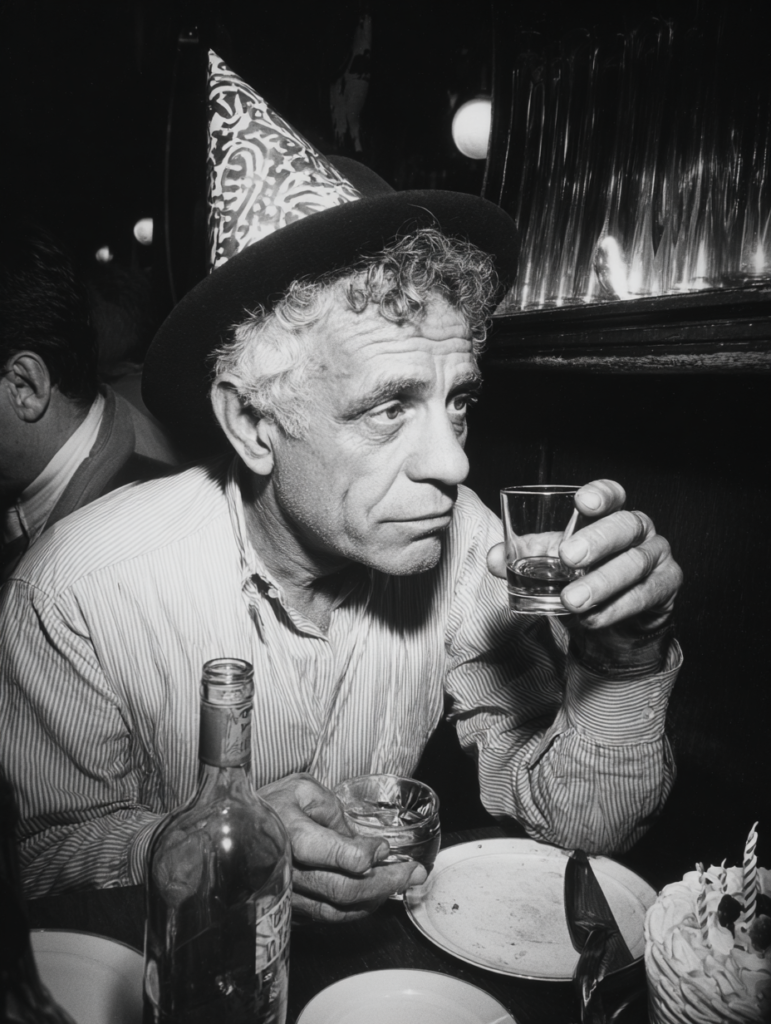

You know what today is, dear reader: The Big Day! So let’s get to it. Let us raise a glass – preferably something volatile, possibly hallucinogenic, and definitely poured from a copper decanter with unnecessary gauges – to the undisputed godfather of speculative badassery. Today marks the 1828 genesis event in Nantes, France, of one Jules Goddammit Verne. [Author’s note: his middle name wasn’t really Goddammit – it was Gabriel – profanity added for enthusiasm.] And frankly, if you don’t think this man deserves a twenty-one-gun salute fired from the deck of a submarine that doesn’t exist yet, maybe you’re better off watching professional sport or some such.

Because this man essentially reverse‑engineered the future using nothing but ink, obsessive research, and a brain wired like a Victorian supercomputer running at unsafe voltages while everyone else was still trying to figure out how to keep their pantaloons from catching fire near a candle.

Verne was doing the heavy lifting before “science fiction” was eve a glint in a publisher’s eye. He looked at the world – a world obsessed with steam engines and top hats – and said, “That’s cute, but what if we shot three guys out of a cannon and landed them on the moon?” And he did it with such meticulous, neurotic research that you almost feel bad for the lesser mortals trying to write adventure stories today. It’s the literary equivalent of building a functioning internal combustion engine out of paper clips and cider-driven hubris.

The man didn’t predict the future so much as he bullied it into existence. Every submarine hatch that ever hissed open in the real world owes something to Captain Nemo’s brooding Nautilus, that gothic iron leviathan gliding through abyssal darkness like a floating cathedral of revenge. Every rocket that punched through the atmosphere carries the echo of Verne’s lunar shell, that audacious brass-and-gunpowder dream. He mapped the thrill of the unknown onto the grid of known fact, and made speculation feel like engineering homework. Verne predicted the electric submarine at a time when electricity was basically just magic that killed you if you touched it wrong. He saw the deep-sea exploration, the crushing pressure, the isolation – he saw it all through a haze of cigar smoke and French ennui.

Consider, sexy reader, From the Earth to the Moon. The man basically calculated escape velocity on the back of a napkin while sipping absinthe. He predicted the launch site (Florida, obviously) and the splashdown method. It’s almost annoying how right he was. It’s the kind of prescience that makes you wonder if he had a time machine stashed in his basement next to the wine rack.

Then there is Around the World in Eighty Days. Phileas Fogg is the patron saint of punctuality and anxiety. The idea of global connectivity, of shrinking the world until it fits in your pocket watch – Verne saw the internet coming. He didn’t call it that, of course. He called it steamships and railways and pure bloody-minded determination, but the spirit is the same. He understood that the world was getting smaller, faster, and infinitely more dangerous.

So here’s to Jules Verne, the man who taught us that exploration is 10% science, 40% madness, and 50% just refusing to admit that going to the center of the Earth is a terrible idea. He is the reason we look at the stars and think, “Hell, I bet I could build a ship and go up there,” instead of just, “Pretty lights.”

Now go build something impossible. Or at least read something that makes you feel like you could.

N.P.: “The King’s Court” – Kristofer Maddigan